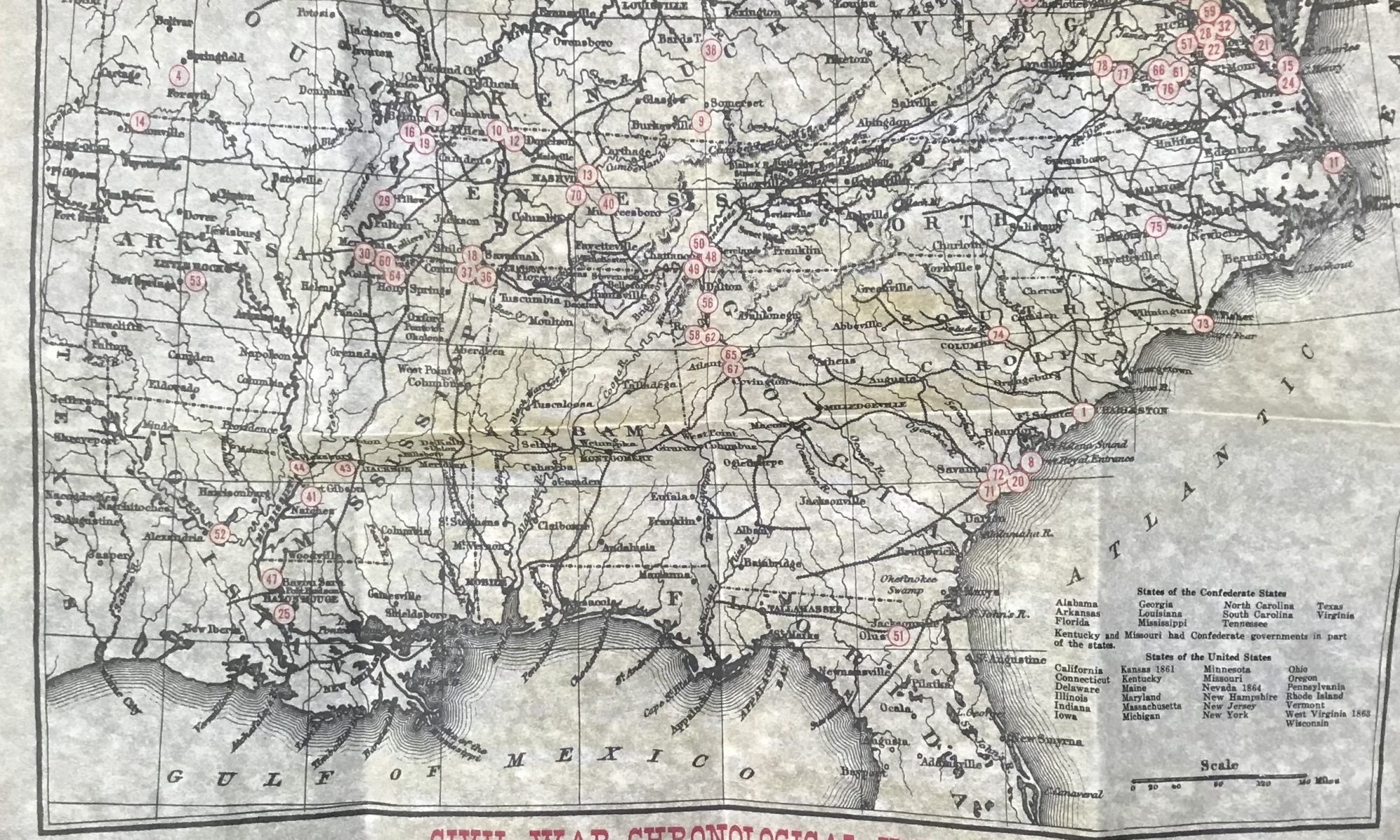

The envelope grabbed me: “Reproduced on antiqued parchment that looks and feels old” (Historical Documents Company, 1961).

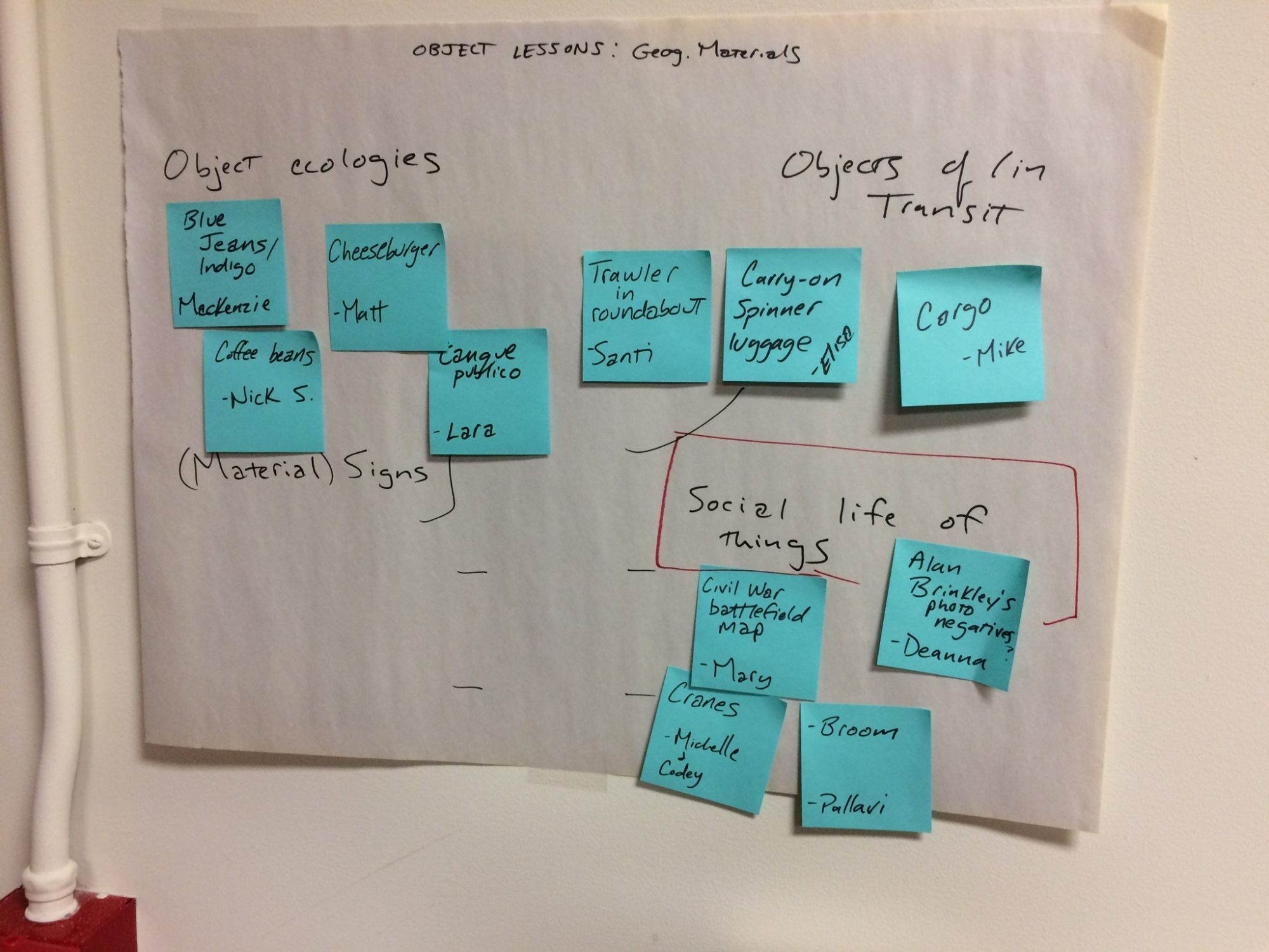

I had come to Bennett Place State Historic Site in Durham, N.C., on a bright October morning. Sharing the space with a middle-aged couple, a group of older women, and a Girl Scout troupe on a scavenger hunt, I made my way through the small museum, along the stops of the self-guided tour, and then back to my car by way of the gift shop. Browsing the overwhelming array of U.S. and Confederate flag-emblazoned mugs, magnets, and T-shirts, I came across the small green envelope that immediately prompted questions. What does “antiqued” mean? What does “old” look and feel like?

In the preface to their collection of objects of the Anthropocene, Mitman, Armiero, and Emmett (2018) write: “Objects have the power to bridge spaces and join times. They can summon all at once the past, present, and future, blending the global and local…” (p. xi). Objects like this map serve as powerful entry points for research precisely because they are embodied relationships, making tangible those networks and connections that shape our structures and inform our thinking but might otherwise remain invisible. They are ideologies, materialized.

Opening the map, I was immediately struck by the crinkly sound of the paper, the way it felt rough in my hands, and the brownish-yellow color of the page that evoked parchment. The map itself, criss-crossed with rivers, troop movements, and state names in blocky, printing press font, shows an expansive view of the American South, from the eastern edge of Texas to northern Florida, and from southern Illinois across to southern Pennsylvania. “Civil War Battlefields 1861-1865” is written in red across the top, flanked by Union and Confederate flags. The map is sprinkled with small red-circled numbers which correspond to the Civil War Chronological History on the lower third of the paper. Descriptions like “11: February 6—Union forces capture Fort Henry on the Tennessee River” (Historical Documents Company, 1961), allow the reader to follow the war’s events both temporally and geographically through and upon the map. The copyright on the bottom left of the page is small but incongruous: 1961, Historical Documents Company.

A quick Google search brought me to the website of the Historical Documents Company.

There, I learned that “antiquing” entails an 11-step chemical process that is presented on the website as a family secret developed in 1926 when a Philadelphia pharmacist spilled some chemicals onto a pile of papers, rendering each sheet “aged, wrinkled, and old” (Historical Documents Company, 2018). His “antiqued” documents were first available (I assume for purchase) at the 1939 World’s Fair. The company now makes over 500 documents. Their top 20 bestsellers include replicas of historical documents like the U.S. Constitution and an “exact replica of Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address, in the former president’s handwriting” (Historical Documents Company, 2018).

My map, however, fits more comfortably with other documents in the top 20, including an illustrated list of American flags, sorted chronologically with historical information about each, and a collection of images and signatures of the first 44 presidents. Like these, my map is not a replica of an actual historical document, but rather a collection of curated information that is marked as “historical” via specific aesthetic criteria: crinkled, yellowed paper; printing press font. Perhaps a better word for it, then, is “simulacrum,” in Baudrillard’s (2001) sense of the word: an object with “no relation to any reality whatsoever” (p. 170). In mimicking something that does not in fact exist—in this case, an old map with data on the Civil War curated with 20th century sensibilities—this object blurs the lines between real and fake, authentic and fabricated, and, thanks to the chemist’s time-compressing process, old and new.

The map does, however, relate to a certain idea of reality. In a study conducted on perceptions of realness by viewers of historical performances at museums, Hughes (2011) finds that perceptions of authenticity were “generally based on a complex awareness of the performance medium and emerged from individual interpretations grounded in spectators’ prior understanding and experience” (p. 134). Exact correlation to the past seems to matter less to spectators (or, in the map’s case, to consumers) than their own expectations and understandings of what history looks and feels like. These expectations, built on “prior understandings and experiences” (Hughes, 2011, p. 134) inform an aesthetic of historical materiality that specifically meets the same expectations by which it is defined. The content is important, and creates its own strategic and culturally infused narrative, but it is the material, aesthetic feel of the map itself, the map as historicized object, that ultimately defines its value – as well as what it means to be historical.

The North Carolina state historic sites brochure (freely available at Bennett Place) proclaims: “If you want to get your hands on history, you can do it at North Carolina’s twenty- seven State Historic Sites” (North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites, n.d.) Here, history is marketed as something personal: something one can do, experience, and consume in specific spaces. The brochure features small photos and content information for each site, and includes a map on which each site is marked with a numbered yellow circle. Much like the numbered battlefields on the Civil War map, cartography transforms history into something accessible, close to home, and consumable for the whole family.

My map, then, is part of a larger movement that invites locals and tourists alike to experience history materially in embodied, immersive ways. Bennett Place is one of these twenty-seven state historic sites, and boasts three structures for visitors to explore, including the parlor in which Generals Sherman and Johnston met to negotiate the terms of surrender for over 89,000 Confederate soldiers in April 1865 (Bennett Place State Historic Site, 2012). These structures, however, are in fact replicas of the original house and outbuildings, erected in 1960 with 1840s materials and “restored to resemble an almost exact duplication of the original Bennett home” (Bennett Place State Historic Site, 2012, p. 3). Like the map, these buildings make explicit the fact that history is always being re-created, and re-materialized. Also like the map, these spaces must be constructed in strategic ways that meet certain expectations, certain aesthetic criteria, in order to be experienced as authentic.

Acknowledging what marks this document as “historical” allows us to interrogate the sources of these cultural cues: Anglo-European logics of archive, history, and the proper way to produce knowledge. In meeting and reinforcing these expectations, the map is part of a dialectic that shapes ideologies even as it draws on ideological expectations of authenticity. Objects, as Mittman, Armiero, and Emmett (2018) remind us, have the power to summon past, present, and future. In drawing aesthetically and materially on the very specific past of printing press and parchment, it is worth asking what futures this map, by its very materiality, is summoning, whose bodies and expectations will fit comfortably in this material future, and whose will be rendered invisible.

-Mary Biggs

References

Baudrillard, J. (2001). Simulacra and Simulations. (P. Foss, P. Patton, & P. Beitchman, Trans.) In M. Poster (Ed.) Selected Writings (166-184). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. (Original work published in 1981). Bennett Place State Historic Site. (2012). Self-Guided Tour [Brochure]. N.P.: n.p. Historical Documents Company. (1961). Civil War Battlefield Map 1861-1865. N.P.: Author. Historical Documents Company. (2018). About Us. Retrieved from http://www.histdocs.com/home/pages/aboutus.php Hughes, C. (2001). Is that Real? An Exploration of What Is Real in a Performance Based on History. In S. Magelssen & R. Justice-Malloy, Enacting History (134-152). Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. Mitman, G., Amerio, M., & Emmett, R.S. (2018). Preface. In G. Mitman, M. Amiero, & R.S. Emmett (Eds.), Future Remains (ix-xiv). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites (n.d.) North Carolina State Historic Sites [Brochure]. Raleigh, NC: Author.