My exhibit is a jhadu or broom. Through this exhibit, I examine the intersection of caste, space, and waste in the Indian Railways. In doing so, I contextualize how materialism not only requires bodies for the production of difference, but also relies on the differences that are produced in different spaces, owing to social relations of caste. Caste along with labor conditions allows for the perpetuation and reinforcement of differences.

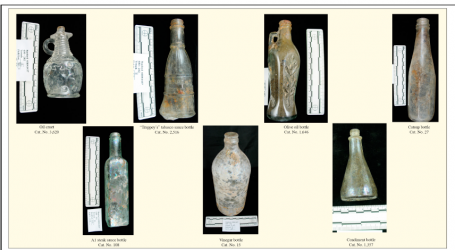

Jhadu or broom performs multiple tasks. The material qualities of a broom have changed with time. However, its symbolic relation with caste remains significant. Caste is the four-tier social stratification of the Indian society(1). With changing technology, different forms of cleaning equipment like hose pipes and vacuum cleaners have come up but the act of cleaning remains central to all of them. And the broom continues to remain pivotal to the process of cleaning despite technological progress and the presence of different types of equipments. Several reasons can be attributed to this, including the presence of rudimentary toilets on the trains; the low salary provided to cleaning staff; and the contractual nature of their work. Further, the gendering of human labor in the process of cleaning is hard to overlook(2). It is evident in the illustration I provide as well.

Through this exhibit, I ask why when so much has changed, so much still remains the same? The contemporary relevance of my exhibit is to examine if material variations in tools can guarantee a change in relationships for all involved and whether material realities alter the unequal relationships inherent in the caste system. Material and economic conditions of the cleaning staff in the railways are related to their caste. The changes in their economic conditions like access to quality education, job opportunities and salary, open up spaces for taking up jobs of their choosing, but the practice of untouchability becomes subtle in such instances. It is some of these aspects that I examine through my exhibit.

The material qualities of the broom also reflect how dirt, space and local cultures are interrelated. Different states in India, have different versions of the broom. Most are made with natural available resources like dried grass, bamboo, dried leaves and branches of trees. The most commonly available form of broom in India use Thysanolaena or broom-grass, a plant belonging to the grass family.

In Rajasthan, India, Arna Jharna, the Thar Desert Museum has different exhibits of hand-made brooms which represent rootedness in the local ecology and traditional knowledge systems of the region (http://www.arnajharna.org/brooms). The museum exhibits highlight the distinction between male and female brooms, and how the task of cleaning public and private spaces are assigned.

With increasing dependence on plastic, the material manifestations of the broom have changed. In the railway station, the gendering of roles gets complicated as the nature of waste to be cleaned is human faeces. The material qualities of a plastic broom, its smooth and non- porous nature eases the process of cleaning. But the act of cleaning is performed by humans, which is both material and symbolic. This act establishes a relationship of difference rooted in caste, labour and gender relations. Most of the labouring bodies who engage with human faeces in public spaces are from untouchable castes. The nature of such employment is contractual and therefore the process of handling waste and cleaning of the railway tracks, allows for reproduction of caste. Even though the practice of manual scavenging has been declared illegal in India, it continues to be practiced in the railway station.

With the help of this exhibit I examine the de facto and de jure aspects related to untouchability in India and connect it to caste-based occupations i.e. cleaning the different sections of the railway station, namely the platform, the toilets, and the railway tracks. I explore how caste determines who gets to clean which part of the station, using what technology (manual vs. mechanical broom) and how this, in turn, perpetuates untouchability.

The broom helps unpack the system of values inherent in the institution of railways. It helps in maintaining cleanliness in the railway station. In doing so, the worker not only cleans the place but also develops a material and objective relationship with the task performed. The act of cleaning becomes more complex due to the overlapping of caste and labor. It opens up discussion on waste, and which bodies are deemed legitimate to handle waste, which is of contemporary relevance to materialism.

In India the broom has transcended spatial boundaries of representation from private homes to being a political symbol. However, it has been unable to break out of the rigid conformities of caste. Thus, the broom becomes a metaphor for understanding the material realities of modernization and its linkages to cleanliness; and helps explain the durability of caste. The broom has become a symbol for the flagship cleanliness project of the Government of India titled Swachh Bharat i.e. Clean India, but it does not challenge the structures of inequality that continue to bind certain communities to these ‘polluted’ tasks.

-Pallavi Gupta

1 More details available on The Laws of Manu, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1886 The Constitution of India designates groups that were earlier known as ‘untouchables’ as Scheduled Castes and the indigenous communities as Scheduled Tribes. Other Marginalized Castes comprise a host of vocation based caste groups that experienced some form of discrimination historically, but which are relatively better-off in comparison to the Scheduled Castes or Tribes. 2 A recent article highlights that there are 95,000 railways cleaning workers involved in cleaning faecal matter from railway tracks and platforms as well as cleaning out railway toilets. 80% are women and the rest are men. (https://thewire.in/labour/manual-scavenging-sanitation-workers)