Introduction

A 100% all beef patty, pasteurized processed American cheese, pickle slices, onions, mustard, ketchup and a bun come together to form the iconic – but a bit mundane when you’re holding it – McDonald’s cheeseburger. Many identities are put onto this object regarding what it is and who it is for. This cheeseburger is popularly described as tasty, addicting, pink-slime filled, ‘food I wouldn’t give my dog’, delicious, and among other associations, a product identified with the hunger of blue-collar workers, low-income households, busy people, road-trippers and convenience seekers. If you’ve never indulged in a McDonald’s cheeseburger yourself, although, chances are you have, your opportunities to are plentiful. In 2014, there were more than 14,000 McDonald’s in the United States and more than 36,000 worldwide cumulatively selling on average 75 burgers every second (Davis, 2014).

Regardless of how the end-product is perceived, behind the cheeseburger is a complex web of relations that make it possible. While what it is and who it’s for can be debated, the product’s assemblage has an undeniably grim relationship with the natural environment, and most of those who prepare and sell it, while it simultaneously produces enormous profits. In this sense, the cheeseburger is also a symbol of mass consumption, destruction, marginalization, and wealth creation.

For these cheeseburgers to be served, for as low as $1 in most instances, a tremendous cost must be levied from the environment, laborers, and consumers. As humans have become a global geophysical influencer in the currently debated proposed human epoch of the Anthropocene, the McDonald’s cheeseburger is emblematic of soaring profits, for some, while issues such as poverty are as deeply entrenched as they were decades ago while dominant economic processes threaten the longevity of planetary life. McDonald’s is far from the only multinational food or non-food corporation that extracts value from the earth and laborers but is symbolic of issues of capitalism, labor, race, and class are paramount to understanding how an unparalleled era of alteration of the earth has occurred and who and what has been most exploited and profited from this process. Focusing on select aspects of the production and consumption of the cheeseburger, we see that it’s price of $1 comes at the cost of the environment, and the laborers who prepare and serve this product while the profit that comes from the production and sales process is concentrated into relatively few hands.

Food production and the environment

Jason Moore’s notion of environment-making to understand the relations of “inequality, power, wealth, and work” (Moore, 2016) provides great insight into how animals, land and people are disadvantaged in the food production process and externalities are passed along to land and the environment for the powerful to accumulate excessive commodities. The burger is produced using a web of resources that previously were perceived as infinite and “cheap” to exploit (Moore, 2016). In this system of infinite resources and cheap nature, the degradation of the environment (and labor) become(s) byproduct of its production and a part of cheap nature itself. Again, McDonald’s isn’t the only business profiting from exploiting the natural environment. According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, agriculture is responsible for 18% of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide which is more emissions than the transportation sector (FAO.org, 2006).

Focusing on the meat of the thing, McDonald’s indirectly bypasses the moral dilemma of raising cattle for slaughter by not raising cattle, but through purchasing, McDonald’s is one of the largest consumers of beef in the world. It takes McDonald’s about 1 billion pounds of beef, the equivalent of 5.5 million cows per year to fulfill the demands for its burger products in the United States alone (Hitt et. al, 2003).

These cows, whose existence is initiated for them to becoming burger products, are raised for slaughter under conditions that contribute to deforestation while they are fed a diet that makes them a potent source of methane gas emissions. In Latin America, it is estimated that 70 percent of deforested areas in the Amazon Rainforest, an area known as an “engine” for absorbing harmful greenhouse gasses (Grossman, 2016), are now used for grazing animals (FAO.org, 2006). A classical economics definition of “externalities” are useful in understanding how this exploitation of the environment is financially unaccounted for. There is no doubt that the costs of these environmental impacts are not absorbed by producers or passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices but are absorbed by earth whose exploitation has proven a cheap method for capital accumulation.

A McBifurcated Economy

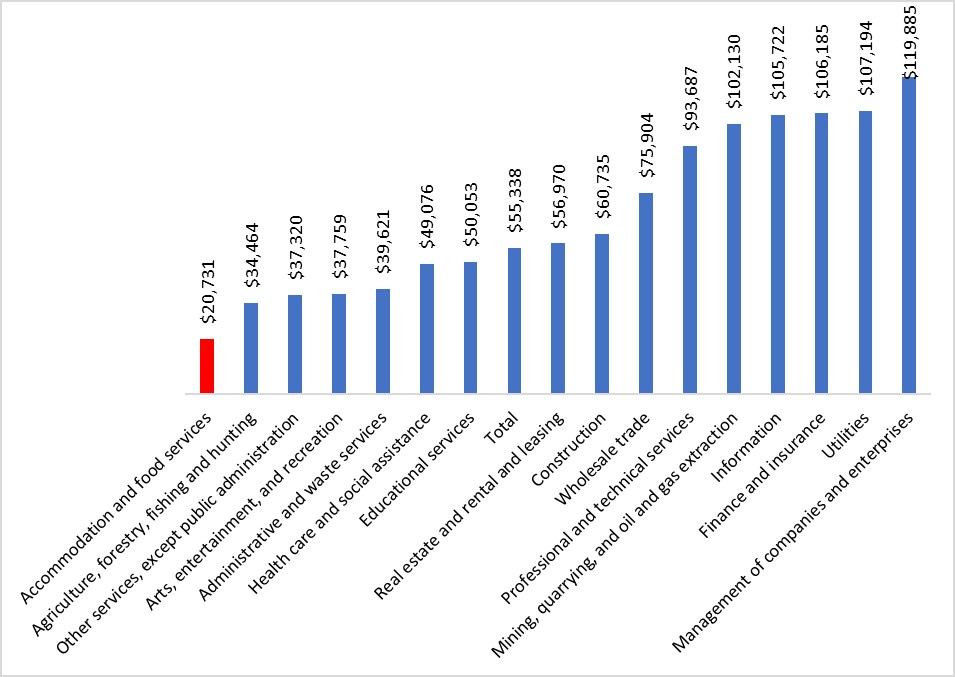

To increase shareholder value and return optimal levels of profit, laborers in the food production and service industries are compensated among the lowest in the formal labor market in the U.S.. Focusing on the end sale of the product, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (2017), the median wage for food preparation and service workers in the U.S. was $9.70 per hour in the second quarter of 2017.

Figure 1 shows the average annual income by industry in 2017. The accommodation and food service industry is the lowest paying in the economy with average annual earnings of $20,731. This average annual earning is roughly $35,000 less than the average for all of the economy.

Figure 1: Average Annual Income by Industry in the U.S., Q2 2017

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Trends such as the Fight for 15 and other living wage ordinances have had varying success at convincing the electorate and policy makers that all work, regardless if you are flipping burgers1, is deserving of a living wage. Companies such as McDonalds have responded to demands from its labor force and general desire to cut costs by automating processes that replace workers such as cashiers (see Figure 2). These types of innovations, and those more broadly in the labor market, have caused economists to discuss a potential future “jobless economy” where advanced robotics and computer systems will replace the need for humans in much if not all of the labor force. In the current U.S. economy, where production outsourcing, free trade, declining union membership, and the retrenchment of a social-safety net have created a bifurcated economy characterized by high-paying high-end services and information technology jobs and low-paying services, the already economically deprived populations in low-paying services are at the greatest risk for losing jobs to automation.

Figure 2: Self-service ordering machines at McDonald’s in New York City (2016).

The pool of finances to pay workers a living wage is flourishing, evidenced by the top 50 fast food franchises seeing over $186 Billion in revenue in 2016 (qsrmagazine.com, 2017). McDonalds, a large part of the fast food ecosystem did over $36 Billion in revenue in 2016 (qsrmagazine.com, 2017) which signifies how large McDonalds and the greater fast-food market are. This figure is even more impressive when you consider the low-cost of products. McDonalds 2017 yearly earnings report touts the company “[r]eturned $2.2 billion to shareholders through share repurchases and dividends in the fourth quarter and $14.2 billion for the full year, marking the successful achievement of the company’s targeted return of $30 billion for the three-year period ending 2016.” (prnewswire.com, 2017).

The Cheeseburger Choice

While some of the costs have been mentioned here, consumers’ health, and environmental impacts of food packaging, transportation, agricultural practices of non-beef products, stores’ electric generation and more should also be thought about alongside the compensation of workers and environmental impacts briefly discussed here. The cheeseburger and the parameters of its creation are a policy choice that enables it to be a viable economic good by not accounting for its “true” costs. The cheeseburger reminds us that we need to look beyond what appears on the surface of a product to understand what we are consuming, who is profiting, and who or what is paying the price.

–Matthew D. Wilson

Footnote

1 McDonald’s kitchens are typically equipped with a double-sided burger grill that eliminates the need for burger flipping but the metaphor still holds.

References

Biermann, F., Bai, X., Bondre, N., Broadgate, W., Chen, C. A., Dube, O. P., . . . Seto, K. C. (2016). Down to Earth: Contextualizing the Anthropocene. Global Environmental Change, 39, 341-350. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.11.004 Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. (2017). Occupational Employment Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/oes/currenT/oes353021.htm Grossman, D. (2016, May 06). Amazon rainforest to get a growth check. Retrieved December 4, 2018, from http://science.sciencemag.org/content/352/6286/635 Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Hoskisson, R. E. (2003). Strategic management, concepts and cases: Competitiveness and globalization. Mason, OH: Thomson/South-Western. Livestock a major threat to environment. (2006). Retrieved from http://www.fao.org/newsroom/en/news/2006/1000448/index.html Davis, L. (2014, August 27). National Burger Day: All your beefy questions answered. Retrieved December 3, 2018, from https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/food-and-drink/national- burger-day-all-your-beefy-questions-answered-9693243.html McDonald’s Delivers Fouurth Quarter And Full Year 2016 Results. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/mcdonalds-delivers-fourth-quarter-and-full-year- 2016-results-300394392.html Moore, Jason W., "The Rise of Cheap Nature" (2016). Sociology Faculty Scholarship. 2. https://orb.binghamton.edu/sociology_fac/2 Steffen, W., Crutzen, P., & McNeill, J. (2007). The Anthropocene: Are Humans Now Overwhelming the Great Forces of Nature? Ambio, 36(8), 614-621. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25547826 The QSR 50. (2017, August 01). Retrieved from https://www.qsrmagazine.com/content/qsr50-2017-top- 50-chart