The bad conditions which formerly existed here in regard to the discharge of lighters, the handling of goods between the wharves and the warehouses, the storage of the goods in the warehouses, and the delivery of same to importers in this city have likewise disappeared… In taking over for a private company, they have not only lowered the charge but also now offer a superior product.(1)

The excerpt above was published by a US customs official in the 1904 report of the US Philippine Commission, the legislative and executive body that governed the Philippines during US colonial rule. In September of 1903, in the infancy of the American regime, the Philippine commission appropriated 39,000 Philippine pesos to purchase what they called the arrastre plant.(2) From the Spanish root “arrastar”, which translates as “to drag”, the arrastre plant was located in Manila’s waterfront port district. With the appropriation of the plant, the government seized control of the process of unloading cargo shipped through the port of Manila. The process of transporting goods and packages from oceangoing vessels to harbor front docks and warehouses, a service that had previously been performed by a private company, was now the responsibility of the US colonial regime.

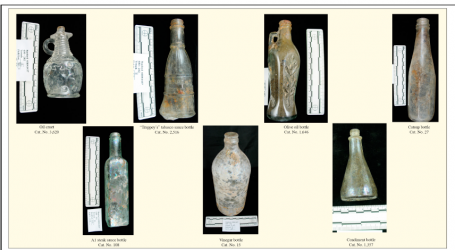

The faded photographs here depict the government arrastre facilities some two years after the government take-over. Published in a pro-American industrialist magazine the accompanying article largely celebrates the efficiency with which goods were unloaded following government reorganization.(3) As an audience, we are immediately drawn to the materiality of the Manila waterfront: cargo, wooden boxes, perhaps a barrel or two, tram tracks, and a hoisting crane. But if the materiality of these objects immediately catch our eye, so to do the men operating the crane, standing near the transport boat, and idling along the tracks. This serves to remind us that as it depends on these boxes, transport boats, locomotives, and heavy machinery, this scene—and the transportation of commodities—is fundamentally constituted by social relations. In this object study, I start from these photographs to begin to consider the complex histories, contested social relations, and living labor that enabled the flow of goods through Manila’s colonial waterfront.

Through these photographs we can begin to examine colonial Manila’s waterfront, docks, and government-owned cargo warehouses as contested contact zones of Filipino-American relations. In these spaces, American industrialists, colonial officials, workers from Manila, and migrant laborers from nearby provinces came together in uneven relations of negotiation, contestation, conflict, and concession. Examining cross-cultural encounters as they unfold in sites like the port provides opportunities to reflect on the contested dynamics of American empire and the labor that sustained it. The government take-over of the arrastre plant and the report excerpted above demonstrate how the process of discharging cargo emerged as a site of colonial governance and managed intervention. During these years American expectations of efficiency and the project of empire transformed waterfront labor time and space into sites of investment. This often took the form of investment in time-saving technologies—handcarts for warehouse workers, new engines for cargo trains, and steam-powered cranes—and the literal production of harbor space—dredging to deepen the port and land reclamation to build new warehouses.

-Mike Hawkins

1 Report of the Collector of Customs for the Philippine Islands, Third Special Report. Prepard by W. Morgan Shuster, Collector of Customs for the Philippine Islands. In Report of the Pilippine Commission, Volume XIII, Part 3, page 538 2 This money was appropriated by Act 897 of the Philippine Commission. 3 “Handling Merchandise at the Manila (P.I. Custom House. September 1905. The Far-Eastern Review, Vol II, Issue 4, p. 100