“Plantations are back”, the rapid spread of oil palm and other ‘boom crops’ has generated renewed interest in the ecological impacts and exploitative labour relations of the plantation complex (Haraway, 2015; Li, 2018). Thinking through the material processes and spatial organization of the plantation “makes one pay attention to the historical relocations of the substances of living and dying around the Earth as a necessary prerequisite to their extraction” (Haraway et al., 2016:557). Yet, relatively little attention has been paid to the ways the material qualities of specific plants themselves reinforce or challenge the capitalist mode of production.

Thinking with planty-materialities brings attention to questions of scale and temporality of land enclosure. The growth cycle and habits of different plant species structure access to land and engender specific labor relations. For example, the Matsutake mushroom forms part of what Anna Tsing calls an “anti-plantation” (Tsing, 2015). The mushroom’s growth patterns and symbiotic relations with certain tree species render it incredibly difficult to cultivate, resisting intensive extraction and the uniformity of mono-cropped plantations. In other instances, plants influence the emergence of capitalist relations, as Tania Li demonstrates by placing the cacao tree at the center of processes of enclosure in highland Sulawesi. Planting cacao serves as a permanent claim to land, one that prevents potential appropriation of fields that would normally lie fallow after seasons of planting sugarcane or corn. The tree serves as a visual sign that the land has an owner.The cacao tree’s ‘permanence’ shapes tenure and labour relations through the need to ensure access to the plant’s fruits over time. Conflicts over the rights to individual trees centers the importance of “everyday processes of accumulation and dispossession” (Hall, Hirsch, & Li, 2011:145). In sum, plants offers a unique way of thinking about access and claims to land.

Coffee (Coffea arabica) is an especially charged object for understanding contemporary plantation spaces. Beyond being a cliche symbol of Western late liberalism’s obsession with productivity and exotic tropical commodities, coffee is a core part of the reinvigorated plantation complex across the global south. Outside of plantations, coffee grows in shady understories of tropical forests and takes several years before it produces fruit for harvest. These qualities present challenges to maximising extraction through monocropped plantations, yet, by selecting for qualities like hardiness and a fast growth rate, coffee growers have bred a plant more conducive to capitalist labour relations but at the cost of biodiversity loss and soil erosion.

Against this form of ‘conventional’ or ‘sun-tolerant’ cultivation, shade-grown coffee is presented as an environmentally-friendly, ‘bird-safe’ alternative. Though shade-grown coffee is also grown in plantations, it is often marketed as an anti-plantation crop that promotes smallholder livelihoods.

Conflicting visions of coffee as a symbol of plantation logic or ecological restoration are especially visible in Haiti, where legacies of the colonial plantation complex coalesce with reforestation projects that center coffee as the solution to environmental degradation. Coffee is a familiar staple of many families’ Lakou, or home garden. The lakou is the spatial center of Haitian home life, it originated as a form of resistance to external control of land through a complex tenure system. As an integral part of the Lakou, coffee helped in forming a counter-plantation system that has been an effective tool for maintaining local autonomy (Dubois 2012). Coffee grown in Lakou gardens blur distinctions between different spaces and modes of production. Coffee’s specific growth patterns play a part in its use as a commodity, an agent of reforestation efforts, and a vital aspect of Haitian home life. Coffee’s material qualities do not necessarily “compel” participation in the market or inherently resist it, but coffee plays an active role in shaping possible ecological and economic futures. Reflecting a range of competing imaginaries, coffee is imbued with strong affective properties that shape landscapes and understandings of place. In this way, plants are sites of subject-making and tied to biologized ideas of identity and citizenship. In other words, plants are not just part of a landscape, plants are tools of place-making.

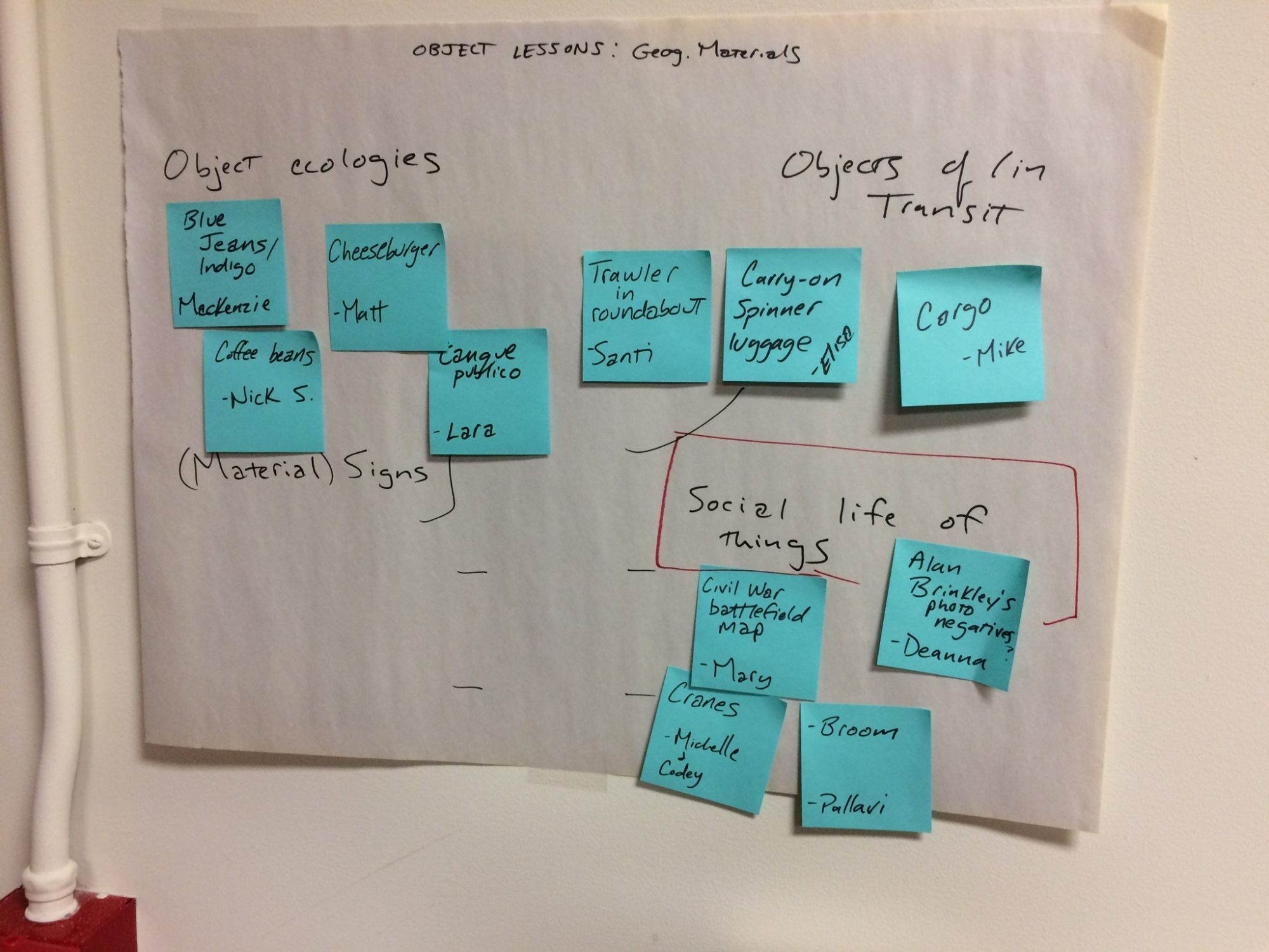

-Nick Scheffer

Works Cited

Carney, J., & Rosomoff, R. N. (2011). In the shadow of slavery: Africa’s botanical legacy in the Atlantic world. Univ of California Press. Casimir, J. (1981). La culture opprimée. Delmas, Haiti: Lakay. Dubois, L. (2012). Haiti: The aftershocks of history. Metropolitan Books. Hall, D., Hirsch, P., & Li, T. (2011). Powers of exclusion. Land Dilemmas. Haraway, D. (2015). Anthropocene, capitalocene, plantationocene, chthulucene: Making kin. Environmental humanities, 6(1), 159-165. Haraway, D., Ishikawa, N., Gilbert, S. F., Olwig, K., Tsing, A. L., & Bubandt, N. (2016). Anthropologists are talking–about the Anthropocene. Ethnos, 81(3), 535-564. Li, T. M. (2018). After the land grab: Infrastructural violence and the “Mafia System” in Indonesia's oil palm plantation zones. Geoforum, 96, 328-337. Tsing, A. L. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist