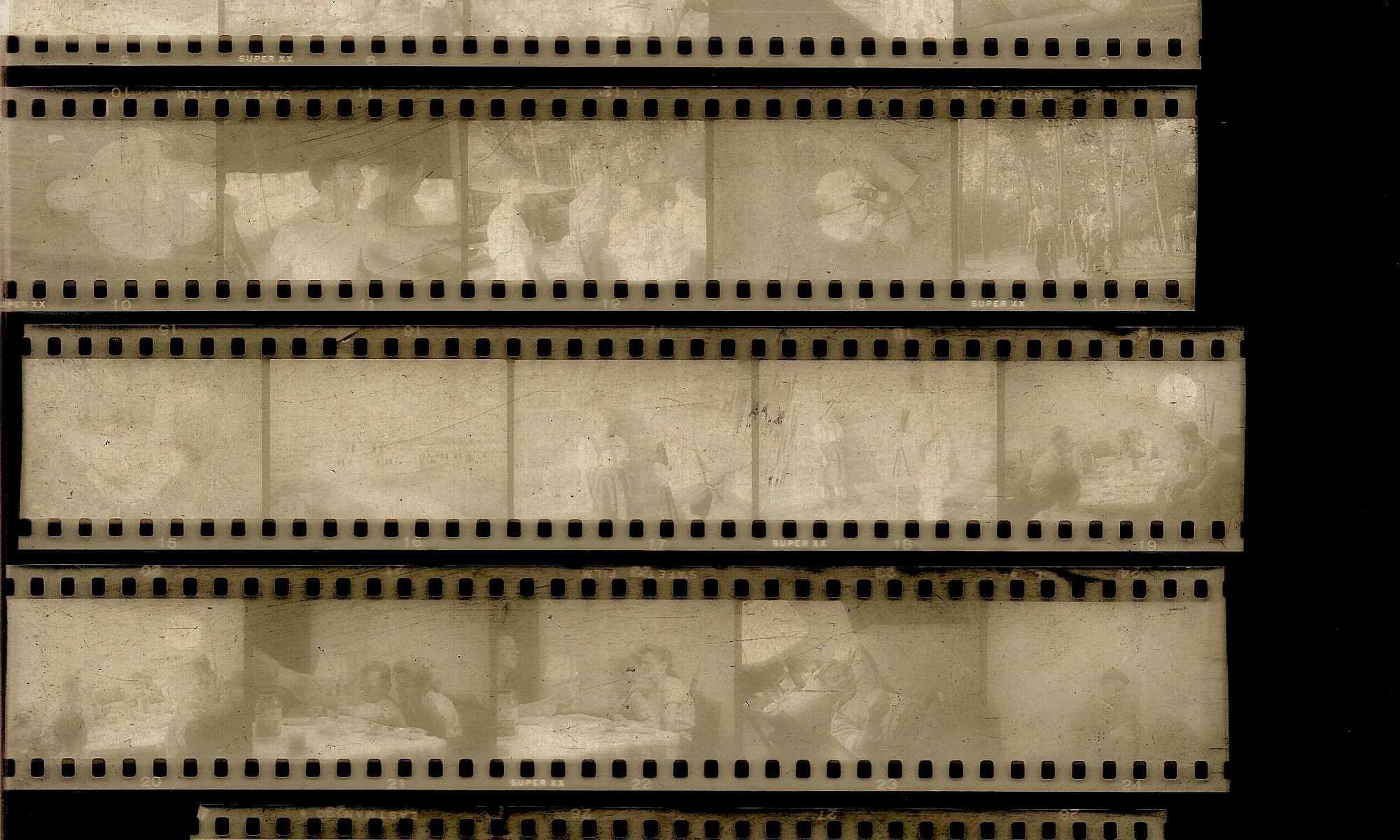

“To collect photographs is to collect the world. Movies and television programs light up walls, flicker, and go out; but with still photographs the image is also an object, lightweight, cheap to produce, easy to carry about, accumulate, store.” (Sontag, 1997: 3)

At an estate sale this past Fall, within a house of 30,000 books, I came across a small box of developed rolls of film. While I was at this estate sale for cheap books I did find myself leaving with a cardboard box labeled 35mm negs containing 28 developed rolls of film. Looking through these rolls of film brought up questions of how photos, or the image, can produce affect and relationality, even out of context. These ultimately discarded objects, negatives of Germany and Paris in the 1950s, unidentified women in hotel rooms, and of young children and familial spaces, share insights into a moment in another’s life and to cultural forms of visual literacy.

These images contained in a roll of film generate certain ideas and questions around temporalities, voyeurism, family, and the relationships between the photographer, those photographed, and the viewer. These rolls are the personal memories of some place, some time, and someone, have been purchased by an interloper, to be viewed, read, and interpreted. As a part of this exhibit, my study looks at a roll of film as an object and how through syntagmatic concatenation a roll of film begins to tell a story, becoming its own exhibit. These stories reveal certain aspects of our visual literacy and could work as an informative study in how meaning is made, as W.J.T. Mitchell states “In order to know how to read it, we must know how it speaks, what is proper to say about it and on its behalf.” (Mitchell, pg. 28). Our engagement and relation to images allows us to make sense of the specific information conveyed even if it is subjectively, historically, and socially situated.

In the contemporary moment film is a tenacious material, with digital media and fewer spaces to process film , it still remains relevant and in use. Inherent in the medium of film, a roll of film is a loosely bounded spatial and temporal concatenation, capturing certain visual flashpoints that produce a type of narrative. Susan Sontag theorizes “Photographs may be more memorable than moving images, because they are a neat slice of time, not a flow.” (Sontag, 17), and these slices, or the boundedness, lends itself to an inherent relationality between the photos found on a single roll of film. These flashpoints, produced out of a particular moment, tell a story that becomes legible through our various ocular epistemologies. This succession of images, unique and original, framed and shot in a particular moment from a particular point of view generates a visually syntagmatic narrative. The semiotic and material entanglements employed in such a reading emerge from an embodied relation to the image. The content or subject of the image may be meaningful to you or you may make meaning of an image. One is still reading the stories that are produced in a roll of film and we make sense of this story through our own ocular epistemologies grounded in social, cultural, and historical processes. Even if this alters the context, reading an image or a roll of film is always altered by our own relationality, “If the photograph cannot guarantee its own fidelity to an originary reality, we may have to seek to establish a kind of good faith in terms of rendering it meaningful in relation to an always unfinished series of modes of understanding and forms of knowledge.” (Peim, 70). The image, specifically the photo, then becomes a type of technology in how we make sense of the world.

This object, as a part of the Materializing Visions exhibit, aims to demonstrate how people, through the myriad of ways we encounter images, begin to develop certain forms of visual literacy. To understand this object we must begin with the story it is telling and how that reveals differences in how we make sense of the material semiotic world. Stories in the roll of film can reveal differences in our ocular epistemologies and the ways we read and create stories through images. To return to the opening quote, the photograph is an object and is also a form of memory, the multivalent nature of this discloses a complex set of relations informed by political, social, and cultural practices. As Susan Sontag said “To collect photographs is to collect the world.” (Sontag, pg. 3), and I find the roll of film, as object, to be a fixed meditation of the material processes of how we make sense of the world through imagery.

–Deanna Duffy

Works Cited

Mitchell, W.J.T. (1986). Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Peim, Nick. (2005). “Spectral Bodies: Derrida and the Philosophy of the Photograph as Historical Document”. Journal of Philosophy of Education. 39: 67-84. Sontag, Susan. (1977). On Photography. United Kingdom: Picador.